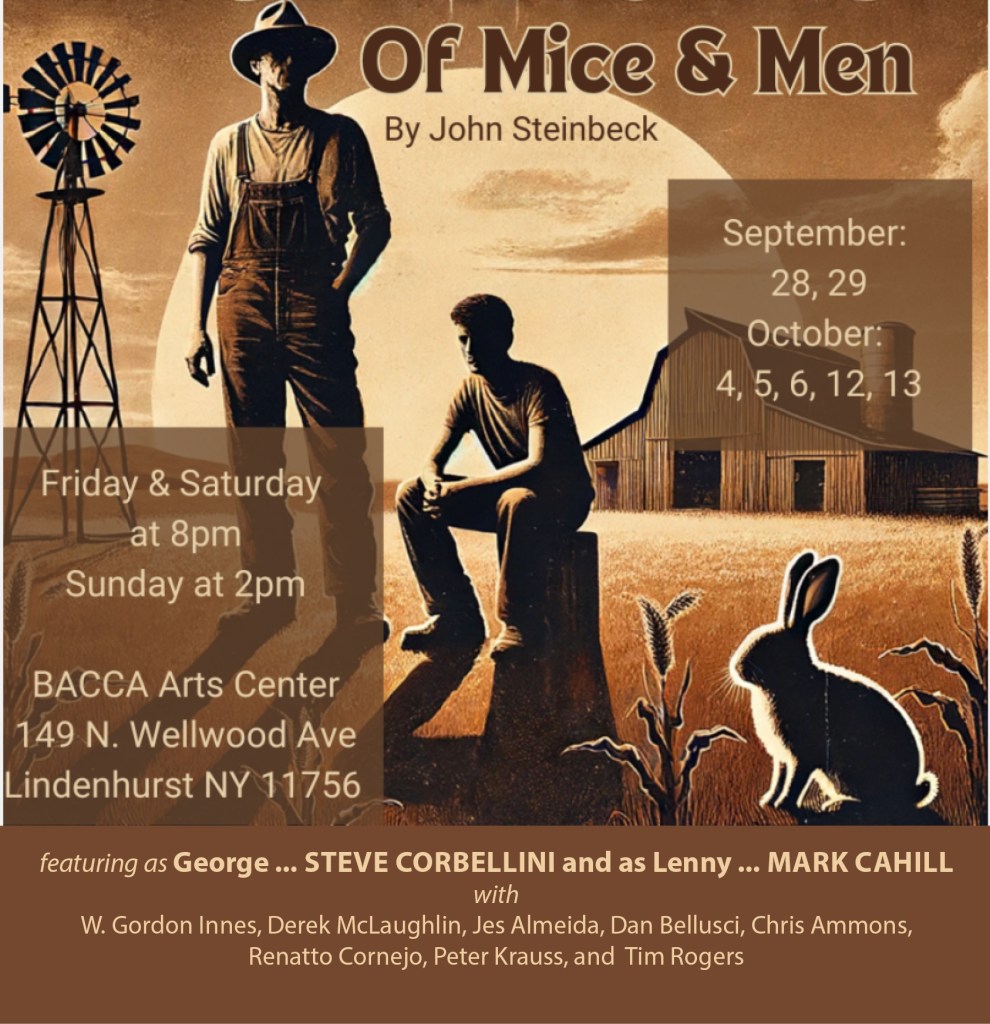

Review: John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, produced by the Modern Classics Theatre Co. of Long Island and BACCA at the BACCA Arts Center in Lindenhurst and directed by Marian Waller. 13 October 2024, 2 PM. By Tony Tambasco

The Modern Classics Theatre Company of Long Island presented John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men at the BACCA Arts Center in Lindenhurst this fall. Adapted from Steinbeck’s novella of the same name by Steinbeck himself, and directed by Marian Waller, MCT’s production made good use of the intimate space at the BACCA Arts Center, and despite missing the mark somewhat on fully realizing Steinbeck’s vision of a cruel world that hardens those who live in it, explored key themes of Steinbeck’s 1937 play that continue to be relevant to America today.

Of Mice and Men tells the story of two itinerant laborers, George Milton (played by Steve Corbellini) and Lennie Small (Mark T. Cahill), trying to make their living in the agricultural valleys of California in 1930. Lennie is a giant of a man with a child-like mind, and George has devoted his life to Lennie’s care. Cahill succeeds in constantly imbuing Lennie with a child-like sense of wonder, openness, and desire for physical touch, which is otherwise absent in this world.

In large part through Cahill’s performance, the effect Lennie has on this world feels completely natural: strong men want to protect him, and the weak are inspired to let their guard down, share their loneliness, and share in Lennie’s dreams. As played by Corbellini, George is a man who has been transformed by Lennie’s presence: as much as he may be tempted to abandon Lennie and the trouble of caring for him, he knows that he draws comfort and strength from their relationship, which he would otherwise lack. George’s bond with Lennie allows him to dream of something more than a fleeting existence in a hard world, and Cahill leans into the ways that George cherishes that relationship, doing wonders to create a sincere bond that Seinbeck never gives him the words to define.

When we meet George and Lennie, they’re on their way to their next job, and when they arrive there in the next scene, they move into a bunkhouse that only gets lonelier as more occupants move in, and where detritus and lice are the only legacy of those who have moved on. Even the ranch they’re working on is owned by a nameless, faceless corporation indifferent to the lives of those who generate its profits. Rian Romeo’s scene design succeeds in embodying this world both thematically and tactilely: stacks of shipping palettes are built in the upstage corners of the stage, with a barrel and a couple of apple boxes thrown in for variety. These pieces are all used as miscellaneous furniture pieces for the bunkhouse, and as architecture within the barn: the two main settings of the play. All of this helps give a sense of not only the overall roughness of this world but also its transience, and reinforces that the human needs of these workers are an afterthought of the people who built this ranch.

The transience of the world, and Steinbeck’s conflation of dream and memory, are also reinforced by the interesting choice to leave less permanent aspects of the scene design visible, even when they are “off.” Bales of hay, a rough bed for Crooks’ room, and a small section of reeds are brought in for scenes requiring them, and the fact that they are visible before and after their use, and we see them so clearly being brought on and off, gives the structures the feel of being ad hoc housing quarters that could be easily repurposed into something more profitable on a whim. The presence of the reeds — the place where we meet George and Lennie, and where the latter is instructed to go if he gets into trouble — is a particularly effective, constant reminder that trouble is coming and Lennie will need to escape somewhere.

The lost hope of this world is on full display as Lennie starts to breathe hope into it. When George and Lennie first meet The Boss (Tim Rogers), he confronts George over his relationship with Lennie, specifically what percentage he’s getting out of it. Slim (Derek McLaughlin), the jerkline skinner (the most respected skilled laborer on the ranch) seems also to be inspired by the same impulse to care for Lennie, as he intuits George’s purpose in doing so. But I find both Rogers and McLaughlin’s performances too open: these two should be some of the hardest men on the ranch because of their power and status, but they connect too easily with George and Lennie on a personal level, and their affability makes me question the meanness of the world that Lennie fears.

Lennie’s openness inspires some of the others to share their dreams: the old hand Candy (W. Gordon Innes) who, overhearing George’s story of the farm he hopes to buy, offers to contribute half the money they need in exchange for a place with them where he can retire. Crooks (Chris Ammons), who is Black and forced to live separate from the rest of the men, is also tempted by Lennie’s dream of a homestead, and dramatizes the internal struggle that most of the other have experienced: he longs for a place to call home, and the chance to create a future that realizes some of the dreams he carries from his youth, but he knows in his heart that it’s impossible for him. The difference between Candy, Crooks, and everyone else is that injury, age (in Candy’s case), and racial segregation (in Crooks’ case) are constant reminders that they have no place in this world. Innes and Ammons both play these characters with a palpable sense of despair, walking a knife’s edge between knowing they’re disposable to their society, while also craving something more than mere survival. The hope Lennie offers Candy seems genuine, but for Crooks, it’s just salt in his wounds.

If there is a villain beyond the meanness of the world or the faceless corporations who are the drivers of so much of it, it’s Curley (Dan Bellusci), who is described as a “small” man angry at the world. Bellusci leans into Curley’s surface meanness but also shows us a side of the character that is weak, pitiable, and utterly powerless, which are facets of this character often overlooked. Curley is mocked for trying to protect some part of himself and keep it soft (literally; he wears a work glove that is rumored to be filled with Vaseline), and his small stature makes him an easy target for everyone else.

Lennie, in turn, becomes the target of Curley’s bullying, with Curley sucker punching him after losing face with Slim and the men. Lennie easily overpowers Curley at George’s command, though, resulting in Lennie breaking Curley’s right hand. The staging of the aftermath of this moment was not well executed, though, as it highlighted Curley’s unwounded hand. One of the characters observes that Curley’s hand is “barely there,” and it is so badly destroyed by Lennie’s grip that a plausible cover story is that Curley caught his hand in a machine. In this staging, however, Curley’s hand is placed front and center to the audience very much undamaged.

I’m not sure if there was a technical malfunction with a blood effect or something of that sort, but in the close proximity of the BACCA Arts Center, we could see there was nothing wrong with it, which is a missed opportunity to make us feel just how dangerous Lennie is. It’s one thing for us to know that he’s killed mice and other small animals accidentally, but if he can so completely destroy another strong man’s hand with so little effort, the horror of that would make us all think twice about wanting him to touch us, putting the audience in the position of the rest of the people of this world. This moment should also give us a little more sympathy for Curley: we’ve seen how a hand lost in an accident has diminished Candy, and Curley is now similarly cut down in his prime, and no longer able to perform masculinity in the way that his world requires, but as staged, the description of the damage comes across as hyperbole, and diminishes the impact of the fight.

The fight, and ensuing consequences, inspire Curley’s Wife (Jes Almeida), the only woman we meet, to leave her husband, and a chance encounter with Lennie alone in the barn initiates the tragic conclusion. Moved by Lennie’s openness and love of soft things, Curley’s Wife invites Lennie to touch her hair; she panics when he lingers too long on it, and Lennie accidentally breaks her neck, killing her instantly.

Despite the observation of Candy and George that Curley’s Wife is a “tart” (the obsolete insult, handled with care by Innes, gets a laugh from the audience that only seems to enhance its power), Almeida plays Curley’s Wife without any obvious flirtatiousness. The performance makes some sense: we have no trouble believing that the men of this world (or our own) will interpret any signs of kindness from a woman as flirtation: we feel like we can take Curley’s Wife at her word when she says that she frequents the bunk house because she’s just looking for someone to talk to. In the context of the meanness of Steinbeck’s world, and the ways he explores performative strength (as opposed to Lennie’s openness), this interpretation of the character doesn’t quite fit thematically, though: we are given vivid descriptions of “cat houses,” and Curley’s Wife links herself to that sort of performance of femininity explicitly when she shares her dream of participating in it by becoming an actress. In the same way that the affability of Slim and the Boss deprives them of a mask of hardness with which to greet the meanness of the world, Curley’s Wife’s constant sincerity deprives her of the mask of feminine softness to the same purpose. Lacking the internal obstacle of a need to perform a public version of oneself despite one’s personal wishes — a recurring theme in Steinbeck’s work — these characters feel less like tragic protagonists of their own stories, and more like ciphers that merely further the tragedies of the more richly developed characters. Since the tragic conclusion of the play ultimately relies on the meanness of the world, and the unique ability of Lennie to inspire hope, these interpretations diminish the overall effect of the story.

After killing Curley’s Wife, Lennie flees to the marsh where we first met him and George; George finds him there, and seeking to spare him a painful death at the hands of Curley’s lynch mob, George shoots him in the back of the head with a gunshot we only hear after the final blackout. If the meanness of the world is not fully inhabited by its reflection in the way that the rest of the cast has reacted to it, killing Lennie is unnecessary: where there’s life, there’s hope. MCT’s production does nothing in its final moments to suggest that we should view Lennie’s death as anything but a mercy killing, and I couldn’t escape the feeling that this was not entirely consistent with the world I saw.

When the world is more open and available, Lennie’s power to open it and encourage people to dream is less significant. When Candy asks George if they can still get their house, George responds that they can’t because that was always a dream he shared with Lennie: in a world that makes people hard, and where the ability to allow them to be vulnerable is special, that makes a lot of sense. In MCT’s production, though, where most everyone is reasonably open anyway, George’s choice to let the dream die with Lennie seems like choosing hopelessness for its own sake.

And yet MCT’s production understands hopelessness well. Candy and George are both destroyed by his impending death and where Corbellini plays these realizations with a varying tempo of thought that gives the sense of his being overwhelmed by a tsunami of feeling, Innes greets the news with a quieter despair, as Candy sees a future for himself little different from Lennie’s. All of these characters understand that there isn’t much for them in the world but suffering; I just wish they had greeted that reality with something more than a shrug.

There are some other components of the production that did not serve it well. Romeo’s scene design makes use of the natural wall of the BACCA Arts Center, and while the irregular shape and color pattern create a visually appealing backdrop, the use of brick creates more of a sense of permanence to the world than the rest of the design elements, which as I’ve noted are made of wood and hay. Another quibble I have with this design is that several of the shipping palettes are of the variety that can be picked from any side, which was not patented until 1945, 15 years after the action of the play, and all of them are built with what is clearly modern lumber and construction techniques, which took me out of the time period whenever the action called attention to them.

If the intention behind those scene design choices was to bridge 1930 and today, it was not reflected in the costume design (uncredited), which seemed a piece of the 1930 setting of the action; nor of the lighting design (uncredited), which was functional. I also don’t think it was necessary to do anything to contemporize the play. Corporations have only gotten bigger and more effective at making home ownership an unattainable dream for most Americans, and while President Biden’s policies echo the New Deal economics that is at play in Steinbeck’s world, we can all too easily relate to a recent economic crisis from which we are still recovering, and the fruits of which are mostly held by the wealthy. And you don’t have to look far to see male loneliness described as both a “crisis” and an “epidemic” in our contemporary press, with similar trends affecting women as well.

We are, in some of the most meaningful ways, still living in the world that Steinbeck wrote about in Of Mice and Men, and despite having better tools available to address baroque economic inequalities and personal loneliness, they often go underutilized because of the same social pressures that George, Candy, Curley, and the rest all face. Nothing works against the quality of life of the working man like the myth that he should be hard, closed off, and self-sufficient: a fact as salient today as it was in the 1930s. MCT’s production comes at a good time to remind us that the comforts we find in this world can be found only in community, companionship, and compassion. Despite some of the flaws I have described, MCT’s production of Of Mice and Men is a powerful reminder that the world will only be a kinder place when we work together to be kinder to one another and value the needs and desires of our neighbors.